On August 21st, my friend Kyle Dempster started up the massive North Face of Ogre II in the Karakorum range of northern Pakistan with Scott Adamson. The two had a harrowing experience on the same peak during their last trip, and they were back to redeem themselves. To do it right, and to do it safely. But a week later, the two were overdue for what was supposed to be a five-day climb, and bad weather had moved in. Family and friends launched a massive search effort which came to include local porters, other climbers in the area, and the Pakistani military.

To fund the effort to find two of our heroes, the climbing community raised nearly $200,000 in a couple of days. Rescues on high, technical peaks in remote regions of the world nearly never end well, but these two are bulletproof. Kyle is without a doubt the strongest person I know, both mentally and physically. His list of big adventures is hard to comprehend. Despite the odds against this turning out well, we all somehow thought that they’d come walking out of the mountains, bone skinny and more tired than any of us would ever experience, but alive and with an incredible story to tell. But when the weather finally broke and the Pakistani military was able to fly, the long searched could not find one trace of Kyle and Scott. I am absolutely crushed.

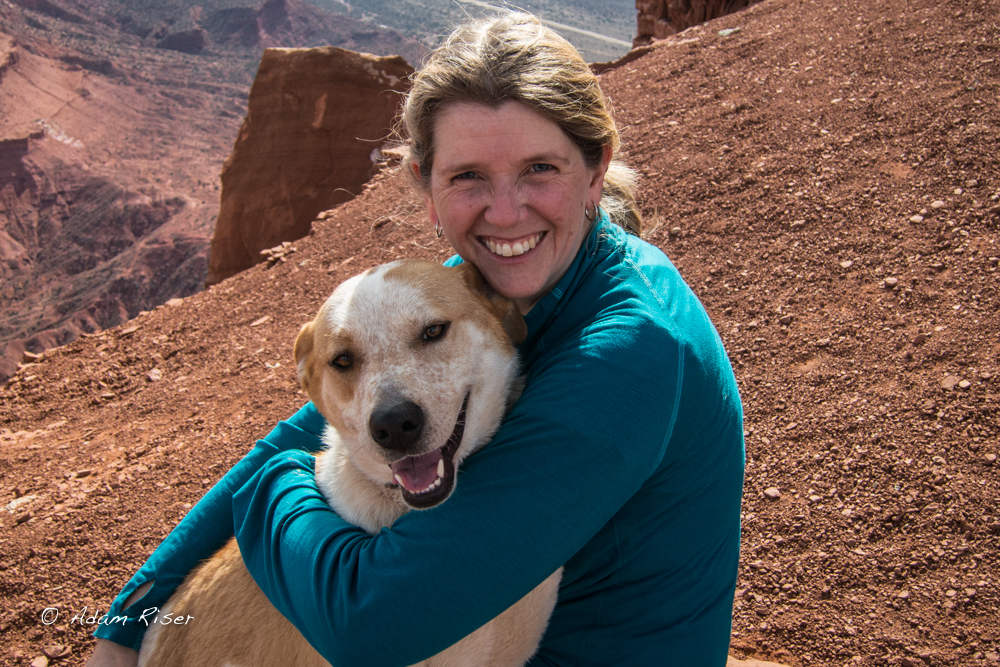

I met Kyle several years ago when he had just started ice climbing. He was brand new to it, and already far better than me. I was going through a divorce, and in the middle of the worst period of my life when we climbed the Fang with a few other friends. It was Kyle’s first WI5, and the day where my regular-life problems finally boiled over into my climbing. I had a complete come-apart during the long day of ice climbing, and made an ass out of myself.

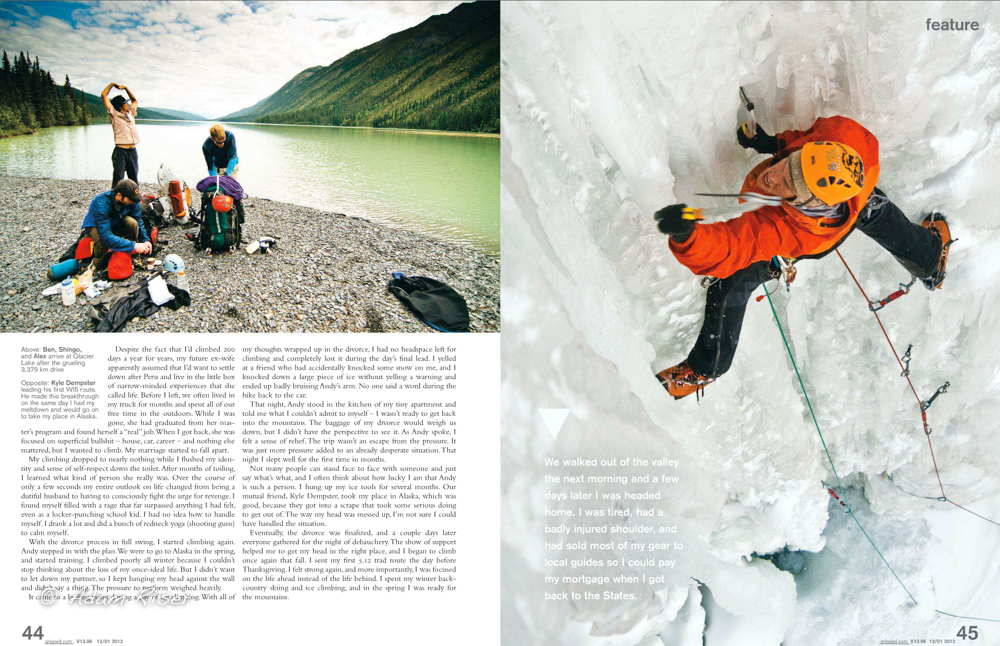

That night my friend Andy stood in my kitchen and did one of the hardest things a friend can do—he told me what I was not willing to admit to myself—that I was not ready to go into the mountains until I had taken care of the thing that was tearing my life apart. We had planned a trip to Alaska that spring, and when I bailed, Kyle took my place. In doing so, I think Kyle may have saved my life. Andy and Kyle found themselves pretty far out on a limb when a snow-ledge collapsed on them while they attempted the peak and Andy and I were going to try. They lost their tent, sleeping bags, stove, and pretty much everything else. So, they down-climbed thousands of feet of mixed terrain with three tools, a shovel, and a couple pieces of gear. In the mental state that I was in, I’m not sure I would have lived through it. To Kyle, the adventure didn’t even rank in the top 10 burly things that he’d lived through.

Not only was Kyle one of the best alpine climbers in the world, he was also a genuinely great person who cared deeply about the friends and family around him. As a way to get his friends together once a year, he came up with the idea of having a barbecue half way up the Great White Icicle during Super Bowl Sunday. He flipped burgers with the Piolet d’Or, the ceremonial ice axe awarded for the most significant alpine ascent in the world each year (he has two of them), and enjoyed the time with his friends. The event is now a Salt Lake tradition.

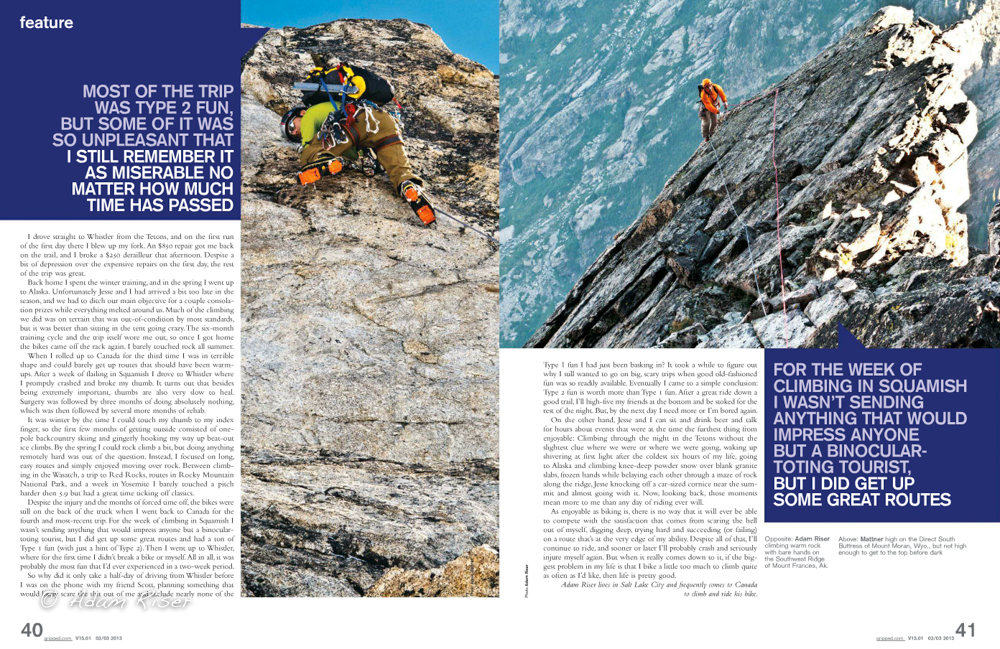

He was always psyched to hear about people’s plans. Just because your dream climb would be his warm-up, it did nothing to diminish how stoked he was that you were getting out and doing something rad. The last time I climbed with Kyle as in Santaquin canyon, where we just happened to run into him tooling around in the Baghdad cave. I was not much of a mixed climber (and am still not), but after he finished doing the first ascent of the long-standing project in the middle of the cave, he convinced me to get on a line that was two grades harder than anything I had ever tried. Kyle just said “Dude, you’ve got that. Just climb it.” and I believed him, so I did.

After Kyle and Scott’s first trip to Ogre II, we ran into each other at Sportsman’s Warehouse of all places. He had just come back from the trip, and after some quick catching up, he started sharing his story from Pakistan. He told me about Scott’s 100-foot lead fall, the broken leg, and the epic descent that followed. Then he said something that really stuck with me. He preceded the next part of the story with “I haven’t really talked to anyone about this yet, but…” and then he told me that near the bottom of the face their rappel anchor failed and they fell 300 feet to the glacier below. When he finished the story, he explained that he was gearing up for bow hunting. He wanted some time alone in the woods to digest what had happened.

It seemed really strange at the time the Kyle would talk to me about the anchor failing when he had yet to share the experience with many of his close friends and family, but I guess it made sense. I think he just wanted to talk to someone who he knew, but wasn’t so close that they’d worry about him. I think even after such an epic experience, he was mostly concerned with how it would affect those who loved him. Years before, when he returned from his solo expedition to Tahu Rutum, 35 pounds lighter and missing part of a finger, he said that the hardest part of the whole trip was seeing how worried his mother was when she picked him up at the airport.

Kyle genuinely cared more about those around him than he did himself. That’s a rare quality to find in even the best people. There is a part of me—the irrational part that believes that heroes are invincible, and if you’re tough enough you can survive anything—that still thinks Kyle and Scott are alive. I would give anything for it to be the case, to hear in a couple days about how they walked out of the mountains. Because the alternative, that the climbing community has lost two of its best, and that I have lost my friend, seems impossible to accept.