Ice is the glue that holds mountains together. Because so much of alpine climbing takes place on either snow or ice, the difficulty of a route (and even if it’s possible) depends a lot on conditions. With poor snow conditions and very little ice anywhere, a lot of the obvious new lines to try were either not safe or not likely to be doable. But, we had one last option that could work. North of our camp were a few East-facing couloirs cut deep into the mountainside and topping out on or near various peaks. The largest of these was a formation called Plum Spire (no “b”), and a 3,000ft couloir went right up the middle of it, ending basically on the summit. It has a few interesting looking steep sections that we scouted with the spotting scope, including the only true water ice that we saw anywhere. Even though the aspect was wrong, we were hoping that the deep walls on either side would protect it from the sun and provide good climbing conditions.

Rick and I geared up with a similar rack as before, but added a full extra set of stoppers to help with the getting down part. We skied to the base, roped up, and started climbing—immediately stoked on what we found. Although the snow itself was terrible, an avalanche had ripped down the middle of the gully and left a 5′ wide trench of excellent neve underneath. The climbing was going to be great.

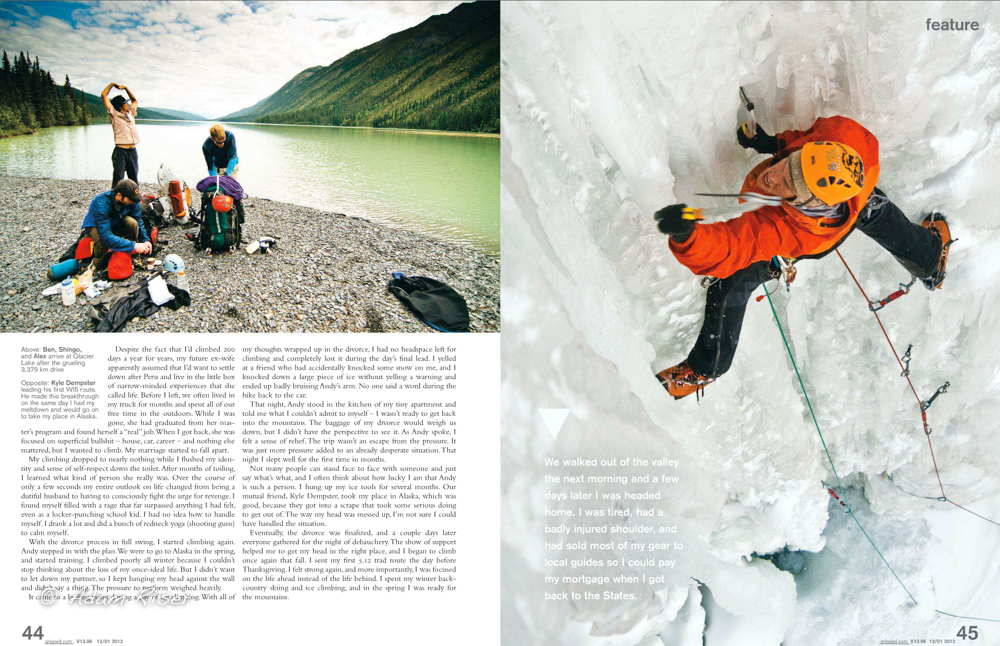

But, our excitement was short lived, as the sky brightened we quickly figured out that although the couloir was deep, it faced directly into the path of the sunrise. In fact, the top of Plum Spire was actually the first thing that the sun hit, and it immediately started showering the gully with shards of ice. We had simal-climbed a few pitches when the chunks started falling, so Rick pulled off to the side and belayed me up so we could decide what to do at a safe spot. Eventually the deluge slowed and then stopped, so we started again. As the sun went up and a new part of the mountain saw first light, the icefall started again. So, I pulled off after a few rope lengths into an awesome cave formed under a fallen piece of rock. In the back of that cave was a piece of old rope left as a rappel anchor. It was the first sign of other people we had seen since we landed. Again, the icefall slowed to a stop, and again we started up. Rick took the block through a short step of ice and we continued up without any gear between us, searching the blank walls on each side but seeing nothing. Eventually he found a hole in the rock with another rope threaded threw it from the previous visitors.

At this point the entire couloir was in the sun, and although the falling debris has stopped the snow was knee deep and super sticky. Each step involved banging boots together in order to clear the snow. A couple more blocks of climbing brought us to one of the coolest features I’ve ever seen in the mountains. A large cave with a 10×15′ floor, nearly flat at the bottom, protected from everything above us, and with an amazing view of the range to the East. So, once again, Rick and I did something we never do in the mountains. We just chilled.

After about an hour of kicking back in the world’s best belay location, we figured that the upper couloir was close to being in the shade, and we decided to make our move. I climbed down and around into the upper gully, which was much narrower and steeper than the climbing below. A couple rope lengths brought me to the base of a large chockstone. It was the first of two that we saw while scouting the route days before, but it was way worse than we expected. This is the spot where the mountain’s glue really matters.

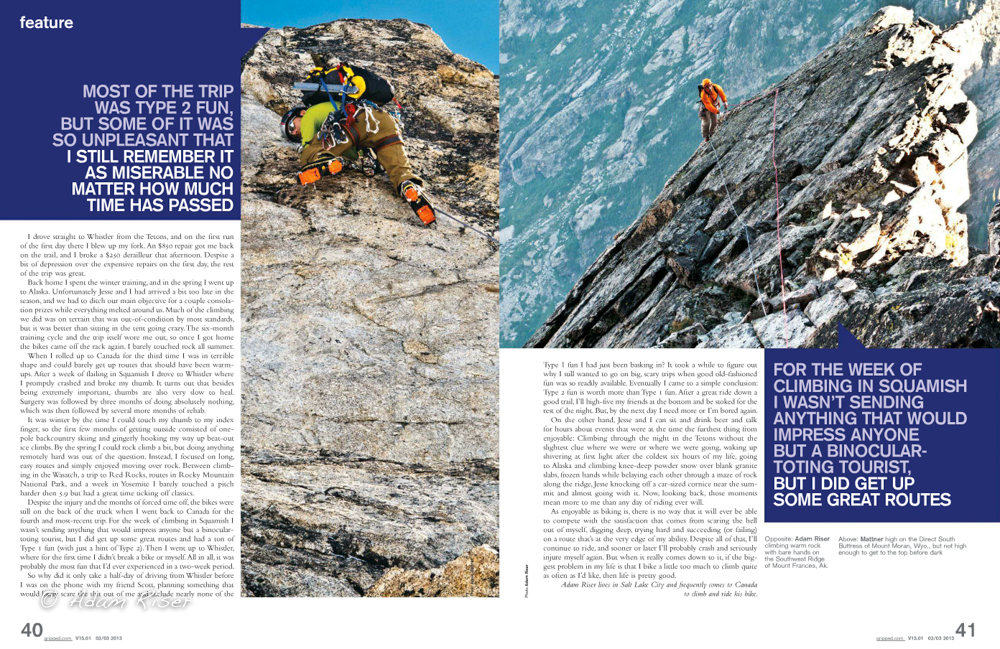

In order to surmount this car-sized boulder, it would require a bit of ice climbing to about 15′ of vertical snow to a 10′ overhanging offwidth to who knows what above. With good neve or a bit of ice on the walls—no big deal. In the conditions we found, extremely hard. Rick went up to take a look and saw no good options. Then I went and found basically the same. Attacking it straight on was completely out of the question. To the right there was a possible mixed variation that I guessed would be M7ish connecting small edges and bottomed seams through a short corner to a slab above. But, there was maybe a single piece of gear in 25ft of very insecure climbing. Plus, we were the only people within about 50 miles in any direction, so this was a bad place to take a fall. We both agreed that the risk just wasn’t worth it, so we turned around approximately two rope lengths from the summit. I regret not being able to top it out, but I don’t regret our decision for a second.

And so began the 17 rappels that got us back to the glacier. Getting off took 13 stoppers, 2 cams, 2 pitons, 18 carabiners, 7 slings, 1 V-thread, 1 picket, and 4 old anchors left behind by the first ascent party. We learned after getting home that the route was originally done by Randy Cerf and Alan Long in 1980, which meant two things: the chockstone could be done in better conditions (or those dudes were just more brave than us), and that the anchors we used were 41 years old. They named the route Plumb Line, which is super fitting. Our whole adventure took us just over 12 hours camp to camp, including the hour we chilled in the cave. It took longer to go down than it did to go up.

As we rested the next day, the mountains continued to melt and we talked through the options. We could basically climb a mountaineering-style route tucked behind Tatina Spire to get to the top of something, but risk missing the end of the weather window and getting stuck there for another week. Or… we could leave, which is exactly what we did. Rick called TAT for a flight out, and at 1:00pm the next day Paul Roderick flew in and scooped us off the glacier. On the way out we picked up a group who was backcountry skiing near Little Switzerland, an hour after that we were having beers at the Denali Brewpub, and a couple hours after that we were back at John Thomas’ house in Eagle River with our flight home booked for the next day. It was extremely strange to go from a week of being completely alone to being around people in such a short period of time.

While it was unfortunately that conditions did not agree with us, but the weather was absolutely amazing for our entire trip. This was without a doubt the most relaxing and least stressful alpine trip I’ve ever been on. I feel extremely fortunately to have had the opportunity to have such an amazing experience in a place where so few people get to visit. The scale of this place, its remote nature, and the potential of routes still to be done is incredible. I am definitely going back.