Most of the big trips I’ve been on were in the planning stage for a very long time. I’ve always had at least six months to train and get all the gear together before leaving on anything that could be called an expedition with a straight face. This one came together in three weeks after Rick and I both had separate trips fall through and found ourselves with a little bit of unexpected time. After tossing around a few ideas, we settled going to the Alaska Range and flying into the Ruth Gorge. There are plenty of routes that can be done in a day, so all we would need was a little bit of good weather to get up a great route or two. As luck would have it, we were able to fly to Anchorage, shop, drive to Talkeetna, and fly onto the glacier in about 36 hours. We unloaded, dug camp, ate food, and decided to rest a day and recover a bit from all the travel and bag wrangling. Our rest day was splitter, and that night we packed gear and set the alarm for 3:00am.

An overcast sky kept things a bit warm, which made it much easier to get up and get ready than we expected. By 4:45 we had eaten breakfast, skied to the base of our route, geared up, and started climbing Shaken, Not Stirred––which is a few thousand feet of mixed and ice climbing to WI5. Rick and I are kind of a strange team. In addition to being a foot taller than me (which isn’t really that special), he’s also a far better ice climber. This allowed me to get out in front and lead the bulk of the pitches while Rick just simal-climbed 200-feet below me. When we got to something that would actually require a belay, Rick would just swing through and knock it out as fast as he could. This worked really well until I was at the top of an 85-degree ice step low on the route and knocked off a giant dinner plate. I yelled a warning as it fell, but after 200-feet it managed to find it’s way directly to Rick’s right arm. I threw in a belay at the top of this pitch to bring Rick up and see how he was, and despite a lot of pain he had no interest in going down, so he swung through for a pitch and I led us to the base of the Narrows.

This five-pitch stretch of steep ice steps is some of the best climbing I’ve ever done in the mountains. The hazard of dropped ice was too great to simal-climb, so Rick took the lead and quickly ran us up through the crux pitches and to the base of the final couloir where we simal-climbed to the col. We arrived at the last anchor 6.5 hours after we started climbing. From the col you can go to the West Summit with about 400 feet of ridge walking. However, when we got there it was a complete whiteout with winds in the 50mph range. Our what-to-do conversation lasted about two sentences, and then we started rappelling.

Back in camp we celebrated in the traditional manner with scotch, Gaiteritas, and bacon. Then we spent the next four days relaxing in camp, visiting neighbors, skiing around, sharpening tools, and waiting for the weather to be clear enough to try another route. Among the groups in camp several climbers from Salt Lake, including a couple guys that Rick knew well, John and Brendan (A couple dudes from Australia who became our drinking buddies in town), Bill and Steve who we flew in with, and Bill Brody, who flies into the range every spring to paint for a couple weeks. The views are amazing, and the only thing you really have to worry about is the weather never clearing or the Ravens eating your foot and pooping on your tent. I polished off my two books and we watched movies on Rick’s tablet, which is my favorite new base camp accessory. On the morning of the fourth day down, the sky cleared and we watched the route all day until we were convinced that we could climb it without getting avalanched. Then, once again, we set the alarm for 3:00am and went to sleep.

As before, we kept our plan for simal-climbing most of the terrain with Rick leading the harder stuff to get us up fast. We simaled through the first two pitches, and Rick swung through to start up the third, which was the first place where we would really be exposed to objective hazards. Being pretty conservative when it comes to things like dying in avalanches, we planned to re-evaluate our situation before every pitch from here on out. Rick took a look, and when we got a ways up the pitch a big, long-last spindrift came off the top and flew over his head. He watched it for a while, let it stop, and decided that it was a manageable risk and cruised through. After I led up several pitches of 50-degree snow, we found ourselves at the bottom of the crux and had to make another decision. This time Rick was in the full brunt of the spindrift for nearly every move. I’ve belayed Rick on some pretty long, hard ice pitches, and I’ve never seen him take so long before. But he kept it together and topped it out with his face packed full of snow. When I followed I got the worst case of scream n’ barfies that I’ve had for years, and we once-again re-evaluated while I growled at the snow and felt my hands come back to life.

The narrow part on this route isn’t nearly as narrow or hard as it was on the other one, so the spindrift didn’t concern us nearly as much now that we were above the business. We swung leads and simal climbed a little bit until we were at the entrance to the upper couloir where we had a bit of a ledge to stand on, change gloves, eat, drink, and generally re-warm ourselves. After our short break, I headed out in front and climbed to the col. The snow was good neve, but spindrift was nearly constant and winds were picking up with each foot of vertical gain. At one point I had to blow the core out of an ice screw to re-place it, and when I accidentally touched it to my lips and it froze instantly. I ripped it away as fast as I could, and blood splattered across the ice in front of me. Luckily my lips were cold enough that I barely felt it.

The last 100 feet were a complete mess. My glasses froze solid, and I couldn’t look into the sprindrift without them, so I ended up climbing in 20 foot sections with my eyes closed. Luckily the neve was great, so I just got into a rhythm of swing, kick, swing, kick and opened my eyes every few minutes to see if I was still on track. As with the other route, there are a few hundred feet of ridge trudging to get to the summit of the Mooses Tooth, and I very badly wanted to be there. However, the weather here was even worse than last time. There wasn’t even a debate about what to do. We just started rigging the rappel.

We were stoked when we got back to camp. With our flight off the glacier coming tomorrow and our two main objectives completed, we celebrated with the last of the scotch, the last of the Gaiteritas, and the last of the bacon. Unfortunately, after packing up camp and shuttling gear to the airstrip the next morning, TAT informed us that they were snowed in and there would be no flights that day. We made dinner a little smaller than usual in case we had to stay much longer, and the next day did nothing for our cause. Instead, it snowed another foot and didn’t stop for well over 36 hours.

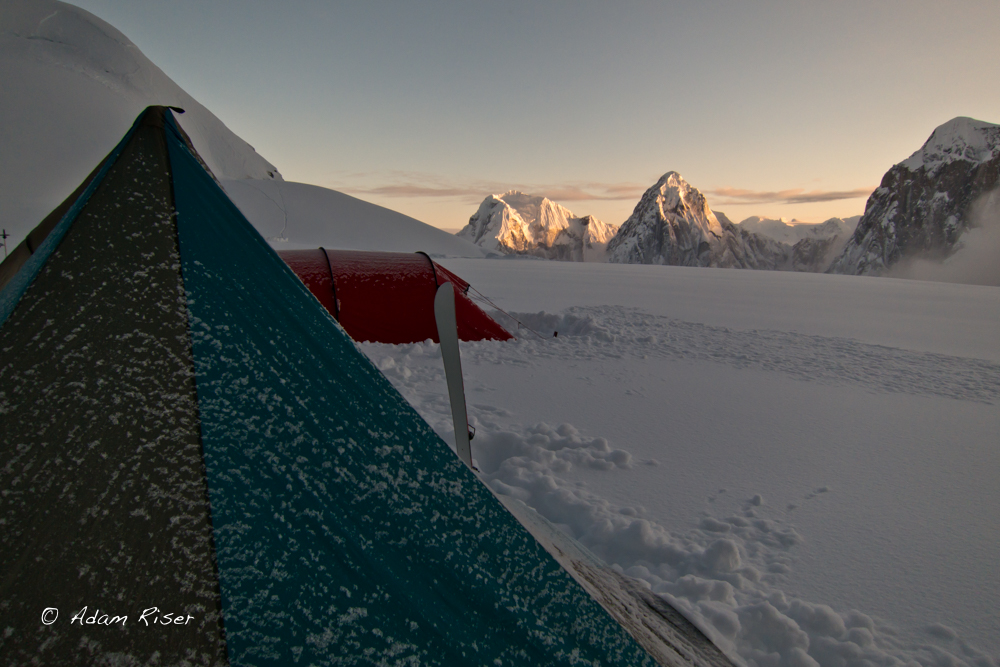

On the third day things were clearing, so we got together with the only other people left in camp, grabbed our skis, and stomped out a runway so the plane would have somewhere to land and take off. It was beautiful all morning while we worked, but Talkeetna was still in a cloud and no one could fly. By the time Talkeetna had cleared, we were socked in, and it was clear that we weren’t going anywhere for at least another night. So, we put the mid back up to eat dinner and play cards with our new friends. Then we pitched the bivy tent (since our main tent was frozen into a ball), crawled into our -20F sleeping bags, and froze our asses off through what was by far the coldest night of the trip. It was worth it just to see the view from the tent when we woke up.

This time we were good to go. The skies were crystal clear and the planes were flying. We had one packet of Mac N’ Cheese left when we tossed our bags into the plane. Unfortunately, our flight back to Salt Lake from Anchorage had already flown two days ago, so in addition to eating food, drinking beer, and drying gear; our time in Talkeetna was spent figuring out how to get home. But the food and the beer was so good that we hardly cared.

Gearing up before the trip.

Rick is huge!

Loading up.

The Ruth from the plane.

Finally on the snow.

The Mooses Tooth (and no, it’s not supposed to have an apostrophe).

View from the tent.

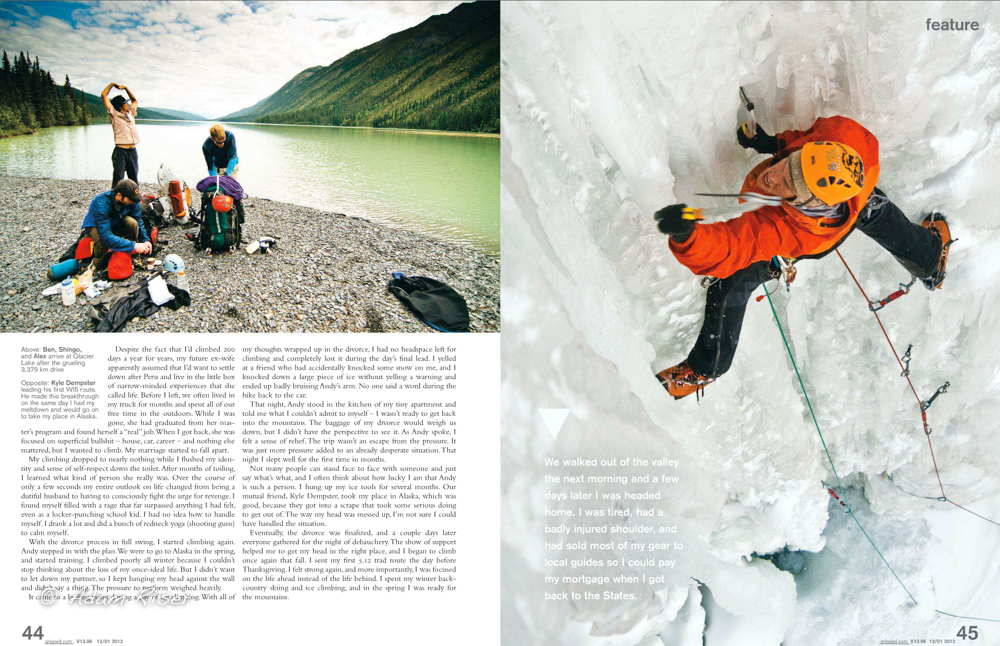

Rick following the first pitch of Shaken, Not Stirred (V, AI5)

In the lower section.

One of the steeper sections on the lower part.

In the middle couloir.

Starting up the narrows.

In the narrows.

This just goes on forever. It’s awesome.

Rick following one of my pitches.

Rick leading the crux.

Gear before the business.

Rick getting a good rest before the steep topout.

Rick high on the route.

My frozen face at the col.

Rappelling.

The storm moved in fast.

Bacon!

Rick chilling in camp the day after the climb.

TAT Turbo Otter flying into the Root Canal.

Rick cooking dinner.

View from the cook tent.

Bill Brody’s painting.

Victory scotch.

Camp in a whiteout.

TAT Turbo Otter under the Mooses Tooth after the storm.

Surface hoar after the storm.

Camp under the first of the snow.

Bill, Steve, and Rick Vance under the Broken Tooth.

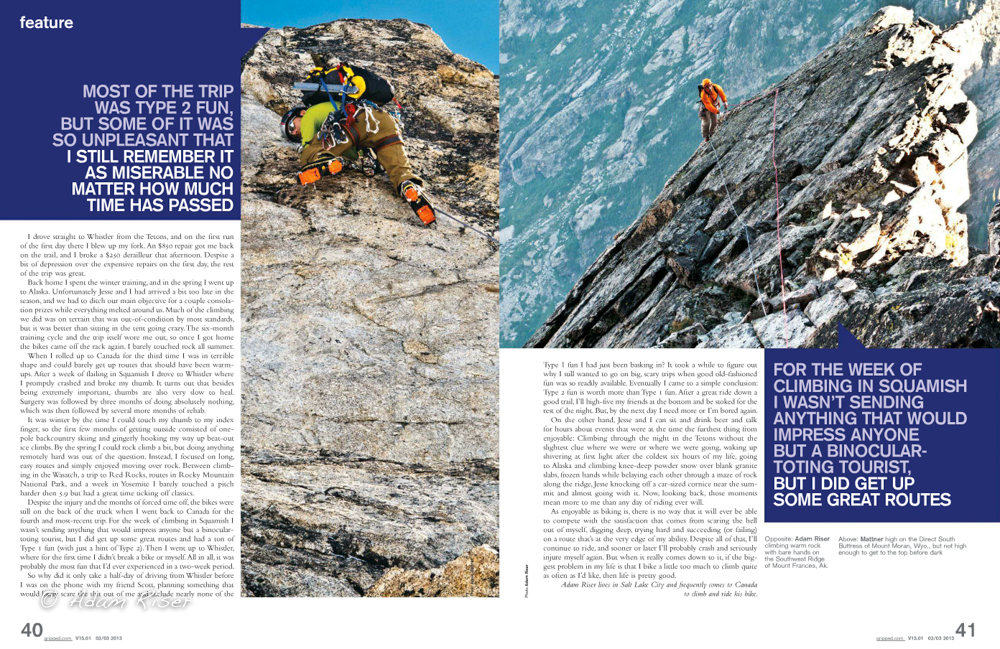

View of the Ruth from the top of pitch 2 of Ham and Eggs (V, 5.9, AI4)

Rick leading pitch 3.

Rick leading pitch 3.

Rick in the upper section of the route.

The last technical pitch.

Rick following the last pitch.

Rick making the first rappell.

Gaiteritas in the cook tent after climbing Ham and Eggs.

The camp under new snow the day we were supposed to fly out.

The tent getting even more buried as the storm continues.

Rick along with our neighbors stomping out a runway.

This took a while.

Party in the cook tent.

Our quickly pitched camp.

Me and Rick. Yeah, he’s about a foot taller than me.

The lower Ruth in the sunset.

Denali from out tent in the morning.

Frost in the tent.

That was a cold night.

Denali and the upper Ruth from camp.

TAT Turbo Otter landing.

My old friend Kurt Hicks landing in the plane set to take us out.

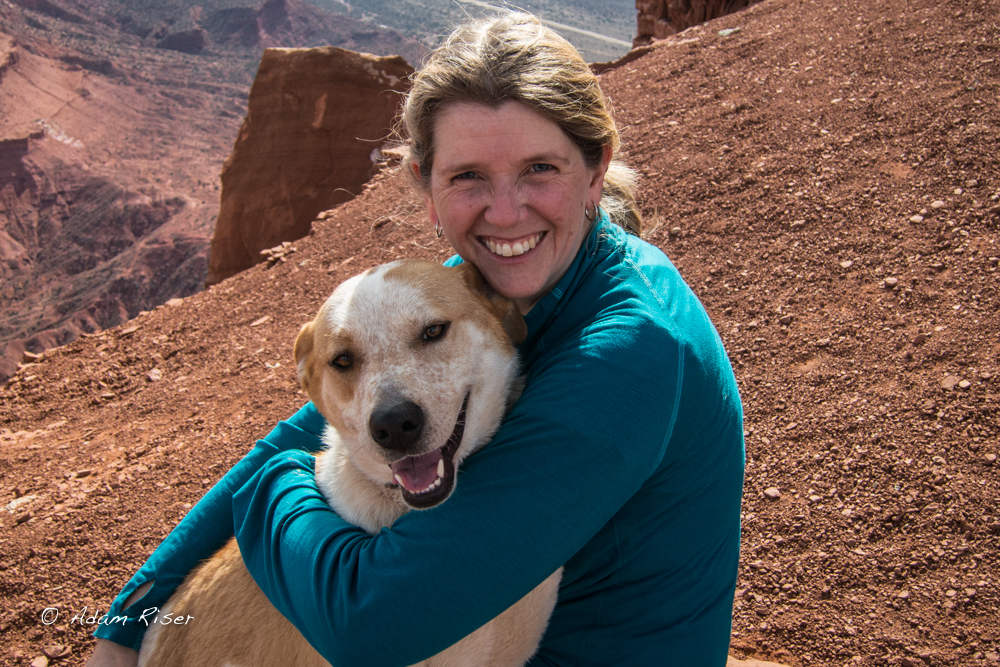

Desert.

The Roadhouse.

Headed home.